Intent specification languages - simplifying network configuration

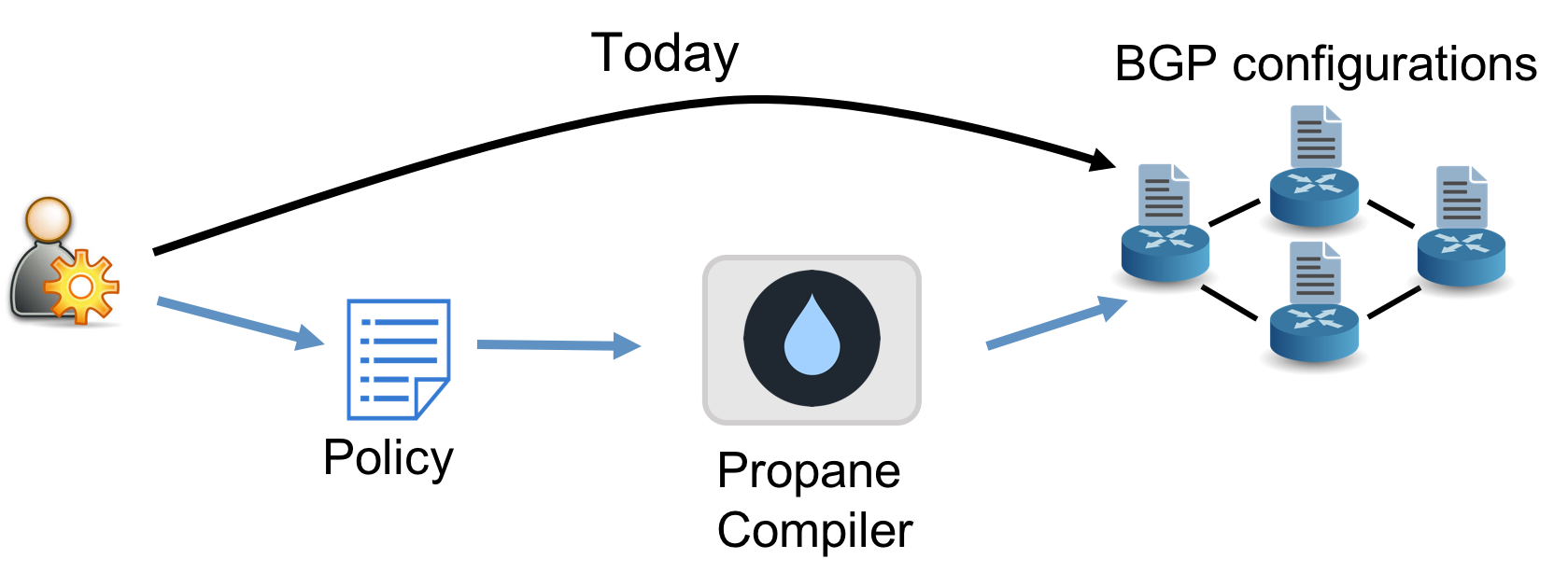

The growing scale and complexity of today’s networks have outpaced network engineers’ ability to reason about their correct operation. As a consequence, misconfigurations that lead to downtime and security breaches have become all too common. In his keynote presentation at Future: NET 2017, Ratul Mahajan, the CEO of Intentionet, introduced a new network engineering workflow to alleviate such problems (see image below). The foundation of this new workflow, formal validation of network configurations, was introduced in a previous blog post.

In this post, we discuss another component of the workflow: languages for specifying network-wide intent. Network-wide specification languages help bridge the abstraction gap between the intended high-level policies of a network and its low-level configuration. Many network policies involve global network properties—prefer a certain neighbor, never announce a particular destination externally-–but network configurations describe the behavior of individual devices. Engineers must therefore manually decompose network-wide policy into many independent, device-level configurations, such that policy-compliant behavior results from the distributed interactions of these devices. This task is further complicated by fault tolerance requirements: not only does a network need to adhere to its requirements during the good times, but it also should forward traffic properly in the presence of a reasonable number of node and/or link failures.

Network-wide specification languages attempt to close this abstraction gap by allowing network engineers to express global network policies directly, with a compiler automatically generating the corresponding low-level configurations. This approach is analogous to the trend in software engineering over the last several decades, which has led to ever-higher levels of abstraction and has been a huge boon for the software industry: Imagine writing today’s complex software in machine code!

Both the academic and industrial communities have been exploring high-level intent specification languages. On the academic side, languages for software-defined networking (SDN) such as Flowlog, Frenetic, Maple, and Merlin allow declarative expression of intra-domain routing policies. These policies are automatically compiled to directives for the OpenFlow protocol, which provides an API to access and update the forwarding rules of each network device. On the industrial side, Cisco’s Application Centric Infrastructure and Apstra’s AOS provide high-level policy languages targeted to data center network design and configuration, along with systems that automatically implement the high-level policies on the devices.

Recently, as part of a research collaboration between Intentionet, Microsoft, Princeton University, and UCLA, we have developed the Propane network-wide programming language. Propane enables high-level expression of both intra- and inter-domain routing in a uniform framework, along with the preference order of paths in case of failures. The Propane compiler automatically compiles these policies into configurations for the BGP routing protocol, thereby leveraging BGP’s distributed mechanisms for routing and fault tolerance.

The Propane compiler guarantees that the distributed BGP implementation it produces will remain compliant with the user’s Propane policy, for any combination of failures. This means that traffic will never be sent along a path that was disallowed by the policy and also that routing will always converge to the best policy-compliant paths currently available. Of course, if there are sufficiently many failures in the network, there may be no available (policy-compliant or otherwise) paths and traffic will be dropped.

In studies of policy we obtained for a data center and a backbone network from a large cloud provider, we have found that we could decompose realistic routing policies into two subparts. One subpart involves definitions of sets of destination prefixes and sets of peers — such definitions may be relatively lengthy but are straightforward conceptually. The second part defines the core routing policy, which specifies the legal paths that traffic to the defined sets of destination prefixes may follow. Surprisingly, we found that the core routing policy of this large cloud provider can be expressed in as little as 30-50 lines of Propane code, whereas the policy requires thousands of lines of low-level BGP configuration. We believe this large reduction in code is one of the key benefits of Propane, making routing policy easier to define, validate, and evolve.

Below we provide a small example to illustrate the Propane language. More information, including a tutorial on using Propane and the source code of the Propane compiler, is available at propane-lang.org.

Propane policies consist of one or more clauses of the form X=>P where X defines a set of destination prefixes and P defines a set of ranked paths along which traffic may flow to reach the given destination. For example, suppose that the network has two peers, Peer1 and Peer2 and that Peer1 should always be preferred for the set of destination prefixes D. The following clause specifies this policy:

D => exit(Peer1) » exit(Peer2)

Here exit(P) represents the set of paths that exit the network at peer P and the constraint S1 » S2 indicates a preference for the set of paths S1 over the set of paths S2. Therefore, this Propane clause specifies that traffic to destinations in D should never exit from peers other than Peer1 and Peer2, and further that this traffic should only exit from Peer2 when no path through Peer1 is available (e.g., due to failures).

Today network engineers must carefully implement such policies through low-level BGP configuration directives at multiple nodes in the network. For example, implementing our example above requires all routers that peer with neighbors other than Peer1 and Peer2 to be configured to filter route announcements to destinations in D that come from those peers. Additionally, all routers in the network that connect directly with Peer1 must assign a higher local preference than those connecting to Peer2. And of course, network engineers must implement these requirements in the configuration language of each device vendor. In contrast, the Propane compiler automatically produces the low-level BGP configuration directives at each node that are necessary to faithfully implement the high-level, network-wide Propane policy.

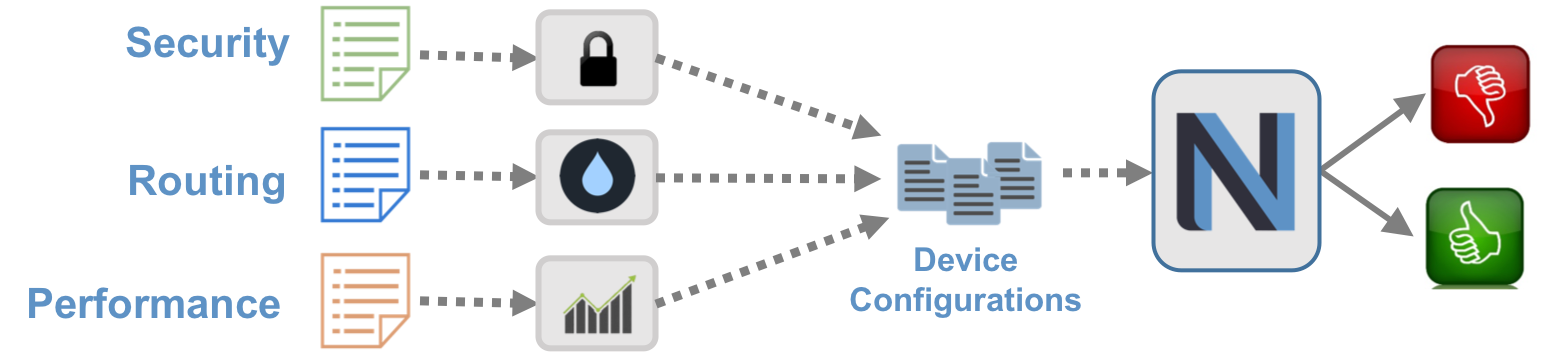

Finally, we note that network-wide specification languages are complementary to tools that validate low-level network configurations. Even if network configurations are generated from high-level policies, the generated configurations still have the potential to contain errors for many reasons, including bugs in the compiler that generates the configurations, errors, and omissions in the original network-wide specification, and manual configuration edits performed by network operators to quickly resolve issues in the field.

Further, network engineers of the future will likely provide multiple high-level specifications, in order to declaratively express disparate aspects (routing, security, performance, etc…) of the network behavior. In such a setting, it will be critical to validate the overall network configurations that result from this combination of specifications.

This is an exciting time as researchers and practitioners explore new approaches to improve and simplify network engineering, such as specifying network-wide intent.