We made networks work. Now let’s make them work well.

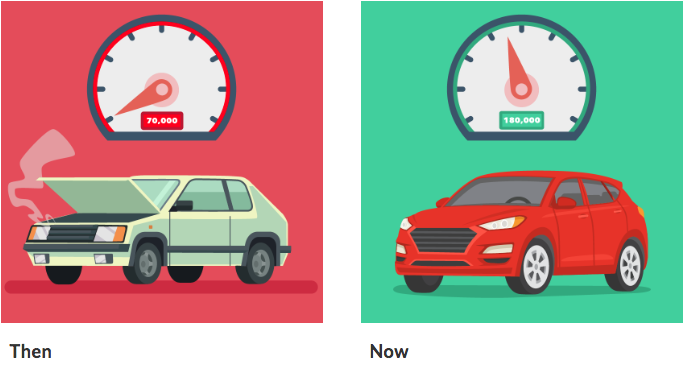

A few decades ago, car odometers were designed to roll over to zero after 99,999 miles because it was rare for cars to last that long. But today cars come with a warranty for 100,000 miles because it is rare for cars to not last that long. This massive reliability improvement has come about despite the significantly higher complexity of modern cars. Cars have followed the arc of many engineering artifacts, where human ingenuity brought them to their initial working form and then robust engineering techniques made them work well.

The computer hardware and software domains have also invested heavily in robust engineering techniques to improve reliability. For hardware, there is an entire industry for electronic design and automation (EDA) tools that help engineers design hardware and provide confidence that the designs are correct before devices are fabricated. Similarly, the software industry has adopted techniques such as unit testing, symbolic analysis, and continuous integration (CI) that help engineers write correct software. In both these domains, investments into correctness were essential to continue to viably engineer increasingly complex systems.

Networking is a reliability laggard

One domain where reliability improvements have lagged is computer networking, where outages and security breaches that disrupt millions of users and critical services are all too common. While there are many underlying causes for these incidents, studies have consistently shown that the vast majority are caused by errors in the configuration of network devices. Yet engineers continue to manually reason about the correctness of network configurations.

The increased use of automation to push changes to devices is a positive trend. But while automation can prevent “fat fingering”, it does not guarantee correctness. In fact, it increases the risk that the entire network will be knocked out quickly by a single, incorrect change. The faster the car, the greater the danger of a serious collision.

It is high time that networking adopted more reliable engineering practices. While the original Internet was an academic curiosity, today’s networks are too critical for businesses and society, and also too complex—they span the globe and connect billions of endpoints—-for their correctness to be left (solely) to human reasoning.

The lack of guarantees for correctness not only increases the risk of outages and breaches but also hurts agility. When engineers are afraid of breaking the network, they cannot update it as quickly as applications and business require. We must get serious about network correctness.

Comprehensive and proactive analysis

We should aim for strong correctness guarantees. The strongest guarantees stem from verification, i.e., comprehensive analysis that can prove that the network will behave exactly as intended in all possible cases. The network will block all packets that it is supposed to block; it will carry all packets that it is supposed to carry, only along the intended paths; and it will continue to do so despite equipment failures. This type of analysis is much more than traditional network validation techniques, such as emulation or grepping for specific configuration lines, which offer no correctness guarantees. In a future post, we will discuss different forms of network validation and their relative abilities.

In addition to being comprehensive, we should aim for being proactive, i.e., check for correctness before changing the network configuration. Comprehensive and proactive analysis can make configuration-related outages and security breaches a thing of the past. It can ensure at all times that access control lists (ACLs) are correct, sensitive resources are protected against all untrusted entities no matter what types of packets they send, and that critical services remain accessible even when failures occur.

Overcoming heterogeneity and large search spaces

Historically, rigorous correctness guarantees for networks have been considered out of reach, but the research community has recently developed promising techniques that overcome long standing obstacles. One obstacle is heterogeneity. There are many (physical and virtual) devices and vendors, each with their own configuration language, data format and default settings. To accurately model network behavior in the face of this diversity, researchers have adapted ideas from the programming languages community, such as parser generators and intermediate representations that are neutral to source languages.

The second obstacle is the vast space of possible cases that must be searched for bugs. There are more than 1 trillion possible TCP packets (given a 40-byte header) and a million possible two-link failure cases in a 1000-link network. To comprehensively and tractably search such large spaces, researchers have adapted ideas from hardware and software verification such as satisfiability (SAT) constraint solvers and binary decision diagrams (BDDs).

The progress in this sphere has moved well beyond theory, and the community has built tools such as Batfish that can guarantee correctness for real-world networks. Batfish is an open source tool originally developed by researchers at Microsoft, UCLA, and USC; engineers at Intentionet, Princeton, BBN Technologies, and other institutions have since made significant contributions to it. Based on network configurations (and optionally, other data such as routing tables) Batfish can flag any violation of intended security or reliability policy.

Today, Batfish is being used at several global organizations to proactively validate network configurations.

Combined with automation, Batfish enables a new paradigm for networking, one where every single change is proactively and comprehensively validated for correctness and only correct changes are deployed.

We now have the means to transform networks from engineering artifacts like older cars, which were not expected to last for 100,000 miles, to ones that we know will work far beyond traditional limits. So, let’s make networks work really well!