The what, when, and how of network validation

When historically tasked with configuring and managing a computer network, engineers have been forced to do almost everything manually: generate device configurations (and changes to them), commit them to the network, and check that the network behaves as expected afterward. These tasks are not only laborious but also anxiety-inducing, since a single mistake can bring down the network or open a gaping security hole.

But now networking is on an exciting journey of developing technologies that aid engineers with these tasks and help them to run complex networks with high reliability. These technologies provide two capabilities: automation and validation.

- Automation augments the hands and eyes of network engineers and helps them log into devices, extract information, copy data, and so on.

- Validation augments their brains and helps them predict the impact of different actions, reason about correctness, and diagnose unexpected network behavior.

These capabilities are conceptually distinct, though some tools provide both. Network validation is the focus of this post.

How well do you speak validation?

There is a wide maturity gap today between automation and validation.

Because it builds on server automation, network automation is more mature and has a well-developed lingua franca. Engineers can precisely describe its different modalities using terms like “idempotent,” “task-based,” “state-based,” “agentless,” etc.

Network validation, however, does not have a nuanced vocabulary. The general term “network validation” gets used to refer to a number of disparate activities, and specific terms get used by different engineers to mean different things.

This lack of nuance hinders the communication and collaboration required to advance network validation technology. That, in turn, harms the adoption of network automation. It is too risky to use automation without effective validation; a single typo can bring down the entire network within seconds.

The faster the car, the better the collision-prevention system needs to be.

In this post, we outline different dimensions of network validation and hope to start a conversation about developing a precise vocabulary. When talking about network validation, there are three important dimensions to consider:

- i) What is the scope of validation?

- ii) When is validation done?

- iii) How is validation done?

The “what” involves three different scopes; the “when,” two simple possibilities; and the “how,” four separate approaches. The choices along these dimensions can effectively describe the functioning of existing validation tools.

What is the scope of validation?

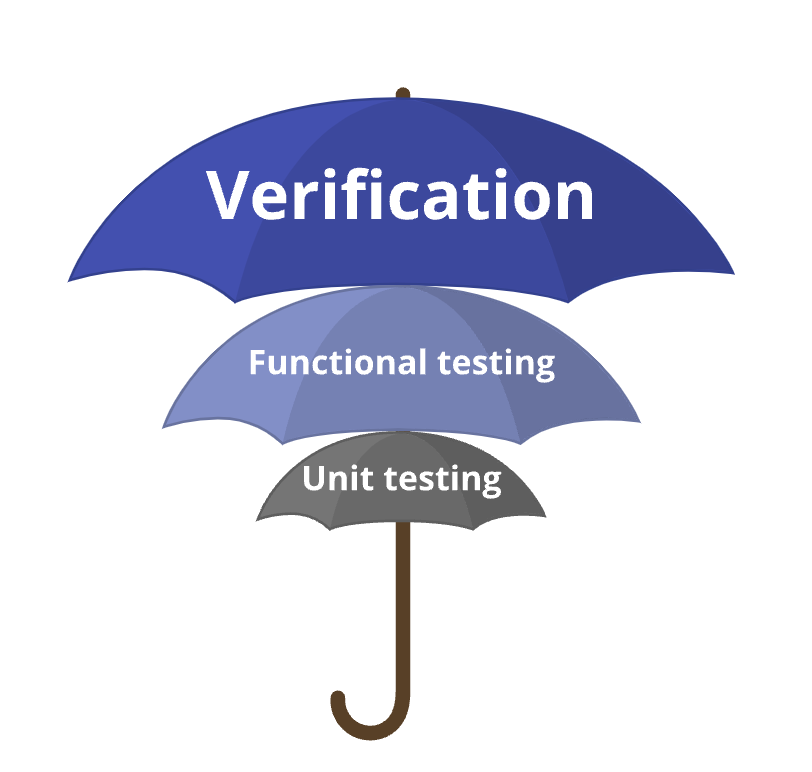

The most critical dimension to consider is the scope of validation, which determines the level of protection. As with hardware and software validation, there are three possibilities.

Unit testing

Unit testing checks the correctness of individual aspects of device configuration such as correct DNS configuration, interfaces running OSPF, accurate BGP autonomous system numbers (ASN), and compatible parameters for IPSec tunnel endpoints.

Unit testing is simple and direct—the root cause of the fault is immediately clear when a test fails— but it says little about the end-to-end behavior of the network. It is not hard to imagine situations where all unit tests pass, but the network does not deliver a single packet.

Functional testing

Functional testing checks end-to-end behavior for specific scenarios such as whether DNS packets from host1 can reach the server, data center leaf routers have a default route pointing to the spine, a specific border router is preferred for traffic to Google.com, and traffic utilizes the backup path when a link fails.

Unlike unit testing, functional testing can provide assurance on network behaviors. However, as with software testing, its Achilles heel is completeness. It provides correctness guarantees only for tested scenarios, while the space of possible packets, failures, and external routes is astronomically large. For packets alone, there are more than a trillion possible TCP packets (40-byte header).

Because it is impossible to test all scenarios, the correctness guarantees of functional testing are inherently incomplete. Just because a few (or even a hundred) test packets cannot cross the isolation boundary does not mean that no packet can. Completeness of guarantees is where verification comes in.

Verification

Verification ensures correctness for all possible scenarios within a well-defined context. It is a formal (mathematical) approach, though the term “verification” sometimes gets incorrectly used for other types of checks. Example guarantees that verification can provide are: all DNS packets, irrespective of the source host or port, can reach the DNS server; the path via a specific border router is preferred for all external destinations; and the services stay available despite any link failure. Such strong guarantees offer network engineers the confidence to rapidly evolve their networks.

When is validation done?

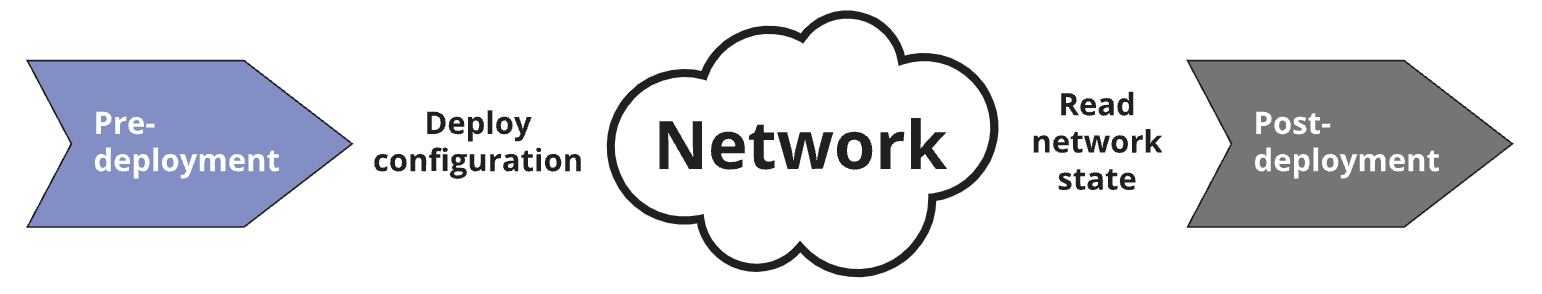

The timing of validation is the second dimension to consider, for which there are two possibilities.

Post-deployment

Validation is done after deploying changes to the network, to check if they had the intended impact. With post-deployment validation, errors can make it to the production network, but the duration of their impact is lowered.

Pre-deployment

Validation is done proactively, before deploying changes to the network. Proactive validation can ensure that erroneous changes never reach the production network, providing a higher degree of protection than post-deployment validation.

How is validation done?

The final dimension of network validation to consider is the validation approach itself. There are four main approaches, each of which is capable if catching different types of errors.

Text analysis

Text analysis scans network configuration and other data without deeply understanding semantics. It can check, for instance, that lines with “name-server” (for DNS configuration) exist and contain specific IP addresses.

Text analysis cannot check network behavior and tends to be brittle. Another line, for instance, could counteract the checked line, but it is commonly used when other options are not available.

Emulation

Emulation uses a testbed of physical or virtual devices (VMs or containers), where engineers can deploy configurations and check the resulting network behavior.

When the emulation and production software is similar, emulation can help predict what will happen in production. However, it is difficult to build a full-scale replica of the production network using emulation either because of limited resources or because software /assets/images of some devices are not available. Using smaller versions dilutes correctness guarantees.

Operational state analysis

In operational state analysis, engineers push changes to the production network and check if they produced the intended impact (e.g., did the newly configured BGP session come up?).

The key advantage of this approach is that it checks the behavior of the actual network. However, it can only support post-hoc validation and will, therefore, leak any errors to the network. Further, it cannot be used to test behavior for scenarios such as large-scale failures because that may disrupt running applications.

Model-based analysis

Model-based analysis builds a model of network behavior based on its configuration and other data such as routing announcements from outside. It then analyzes it to check behaviors in a range of scenarios. It is a broad category that includes simulation as well as abstract mathematical methods. Its two formal variants have been previously covered here.

Model-based analysis is the only approach that can perform verification because evaluating all possible scenarios needs a model (though not all model-based tools support verification). A key concern with it is model accuracy. But as we know from other domains, such models get better than human experts over time, and they need not be completely accurate to find errors.

Comparing validation approaches

Different validation approaches are capable of finding different types of errors. The class of errors found by text analysis are a subset of those found by other approaches.

While model-based analysis can consider the widest range of scenarios, operational state analysis can find bugs in device software that model-based analysis cannot.

Errors that emulation can find overlap heavily with operational state analysis, though it can help find device software bugs triggered by failures often difficult to study in the production network. Similarly, operational state analysis can find errors that emulation misses because emulation is rarely able to faithfully mimic the size and traffic conditions of production networks.

Classifying existing tools

The table below classifies some open source tools along these dimensions.

| What | When | How | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Batfish | Verification | Pre-deployment | Model-based analysis |

| GNS3, vrnetlab | Functional testing | Pre-deployment | Emulation |

| ns-3 | Functional testing | Pre-deployment | Model-based analysis |

| Ping, Traceroute | Functional testing | Post-deployment | Operational state analysis |

| rcc, most homebrew scripts | Unit testing | Pre-deployment | Text analysis |

| Scripts using NAPALM+TextFSM | Unit testing | Post-deployment | Operational state analysis |

Summary

In this post, we outlined the rich space for network validation in terms of its three key dimensions: scope (what), timing (when), and analysis approach (how).

We did not address the important question of which option(s) to pick for a given network. The answer is not as straightforward as picking the “best” one within each dimension. For instance, while model-based analysis provides the strong guarantees for configuration correctness, coupling it with emulation or operational-state analysis may be needed if bugs in device software are a concern. Further complicating matters, the choices are not completely independent because some combinations such as emulation and verification are incompatible.

In a future post, we will outline how to make these choices and implement network automation plus validation pipeline to effectively augment engineers’ hands, eyes, and brains. Such a pipeline would enable engineers to evolve even the most complex networks with confidence, without fear of outages and security holes. Stay tuned!