Designing a Network Validation Pipeline

The networking industry is on an exciting journey of automating tasks that engineers have historically done manually, such as deploying configuration changes to devices and reasoning about the correctness of those changes before and after deployment. These capabilities can tame the complexity of modern networks and make them more agile, reliable, and secure.

Success on this journey requires effective pipelines for network automation as well as validation. Network automation focuses on the mechanical aspects of engineers’ tasks such as generating device configuration, logging into devices and copying data. Network validation focuses on analytical aspects such as predicting the impact of configuration changes and reasoning about their correctness. Automation and validation go hand-in-hand because automation without validation is risky.

If automation is a powerful engine that helps a car go fast, validation is a collision prevention system that helps it do that safely.

Because much has already been written about network automation, we focus on network validation. Previously, we discussed different dimensions of network validation and the options available within each. We now discuss how to combine those options into an effective network validation pipeline. But first, let’s recap the prior discussion, which you can read in detail here.

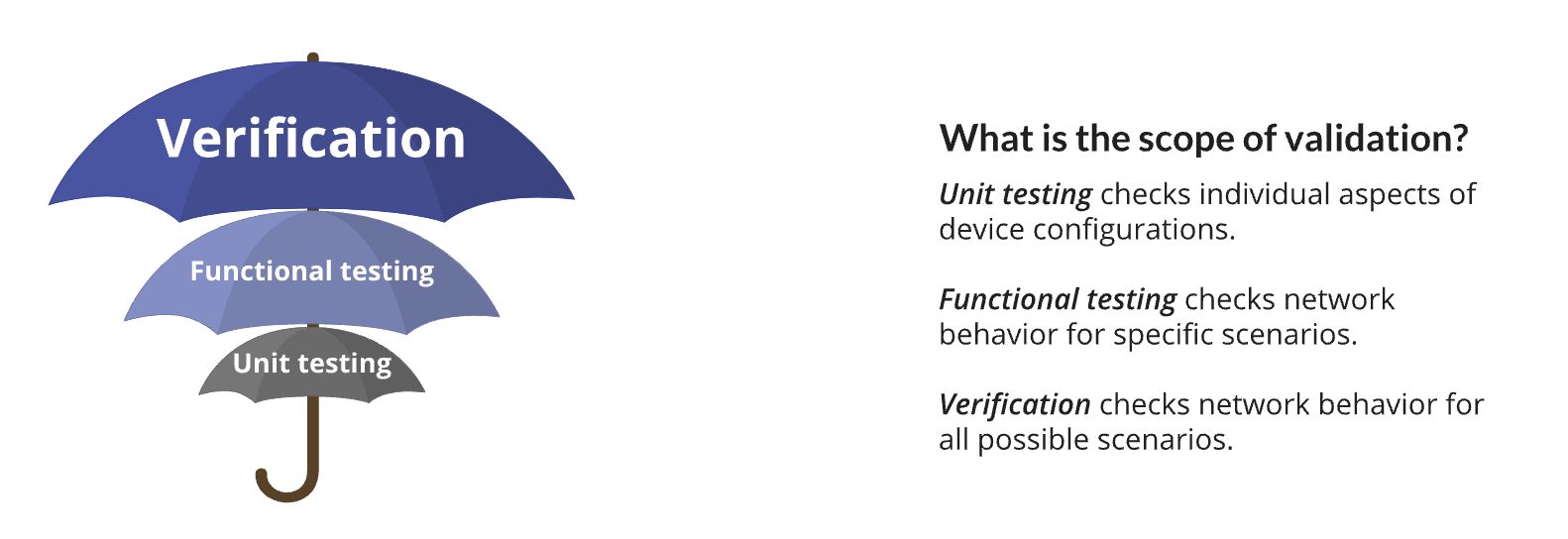

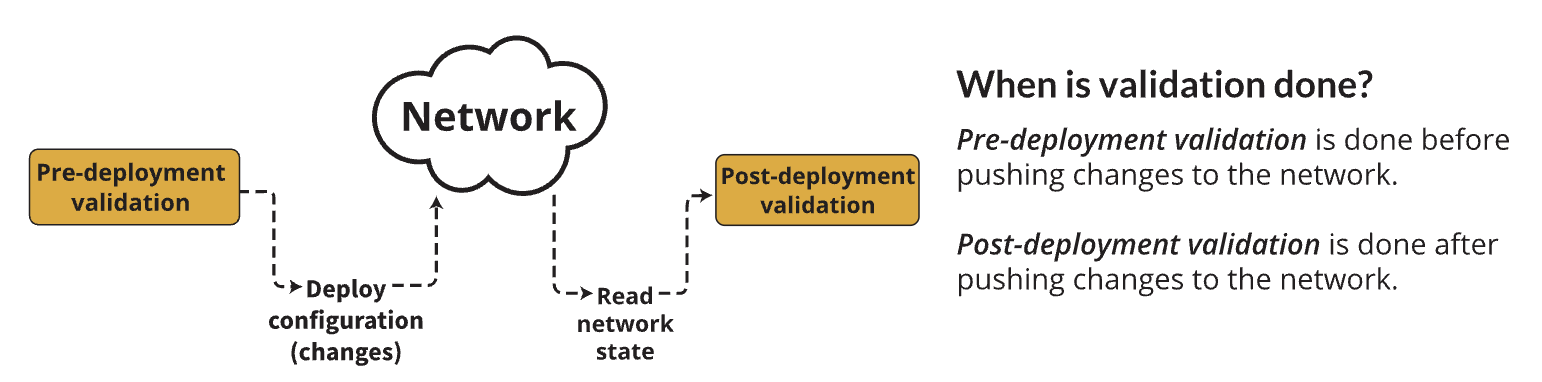

Recap: The what, when, and how of network validation

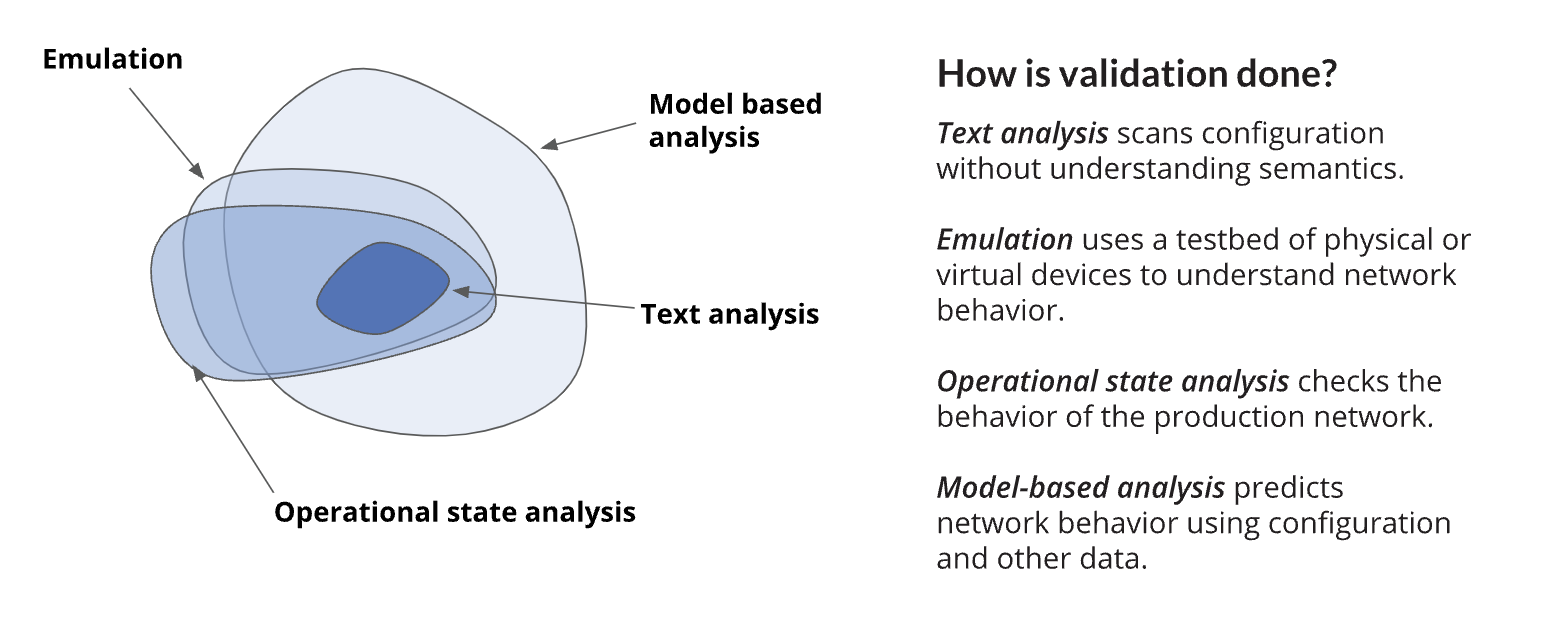

We call the dimensions of network validation what, when, and how These correspond to the scope, timing, and approach used for validation.

Factors to consider

When designing a network validation pipeline, two important factors must be considered.

Coverage: Coverage refers to the types of errors or bugs that the validation pipeline can find. Higher coverage is, of course, more desirable. The “How” figure above provides a guide for thinking about coverage. It shows the classes of issues that different approaches can find. Model-based analysis covers the widest range of scenarios, but emulation and operational state analysis can find unique classes of issues, such as bugs in device software.

The coverage of emulation and operational state analysis overlaps heavily, though each approach can find some unique issues. Emulation can help find device software bugs that are triggered only under failures because we wouldn’t want to induce a failure in the production network to study its impact. Operational state analysis can help find bugs that are triggered only at a specific scale or traffic conditions that are difficult to emulate.

Issues found by text analysis are a subset of those found by other approaches. We thus exclude text analysis from our recommendations below. However, if other validation approaches are not available, text analysis is better than no validation.

Resources: A validation pipeline that requires fewer resources is preferable. Emulation is resource hungry because it needs VM or container /assets/images for production devices and a physical or virtual testbed on which to run these /assets/images. The size of the testbed depends on how closely we want to emulate the production network. On the other hand, approaches like model-based analysis can work with a single well-provisioned server.

Validation pipelines

With these factors in mind, we outline three pipelines. The first one is optimized for coverage, the second one for resources, and the third one balances the two. All pipelines allow us to find issues with configurations errors (design bugs) as well as device software bugs, though they differ on when and which types of issues are covered.

Coverage-optimized pipeline

The figure above shows a validation pipeline that optimizes for coverage. It chains model-based analysis, full-scale emulation, and operational state analysis for verification, functional testing, and unit testing, respectively.

-

Model-based analysis: Model-based analysis is first in the pipeline because it can quickly find configuration errors and has the broadest coverage. This leads to a faster development cycle. As soon as a candidate configuration is generated, it can be verified for correctness using a battery of checks, akin to testing software as part of the build process. If a check fails, new candidate configurations are generated and the process repeats. Model-based analysis allows you to check the expected behavior of the network. Some of these checks may be specific to changes being made, such as:

- Will the newly configured BGP session actually come up?

- Will the ACL change allow users to access the new web server?

Other checks may ensure adherence to overall network policy, such as:

- No packet should traverse between two isolated subnets.

- No single link failure will result in a critical service becoming unavailable.

- Full-scale emulation: We next perform functional testing in an emulation environment that replicates the production network. Emulation is typically limited due to resources and execution time, and only a limited set of test cases can be executed. However, since model-based analysis has already eliminated configuration errors, we can optimize the tests conducted using emulation. In particular, emulation should focus on validating the device software and ensuring that configuration changes do not trigger device software bugs. We run functional tests that check, for instance, that:

- Selected flows are blocked or forwarded as expected (typically done by using ping or traceroute).

- Traffic fails-over as expected after a link or node failure.

- Device functions properly under varying traffic loads (typically done using traffic generators).In addition, coupling emulation with model-based analysis can improve the coverage of software bugs. In particular, we can compare the routing and forwarding tables of every emulated device with what is predicted by model-based analysis. If the two agree, we get stronger guarantees than with emulation alone. Disagreements point to a device software bug (or to a modeling inaccuracy that needs fixing).

- Operational state analysis: Finally, we deploy the configuration to the network and use operational state analysis to ensure that changes are pushed correctly and produce expected behavior. Given the validation that has occurred earlier, we can perform quick unit testing in this step, such as:

- Check that the configuration on the device is identical to what was pushed.

- All expected interfaces are up.

- All expected routing sessions are established.

Resource-optimized pipeline

Emulating the full production network is not always viable because VM or container /assets/images may be unavailable or do not match the capabilities of production devices in terms of supported features or interface types. An alternative pipeline, shown below, can be used in such settings.

- Model-based analysis: Like the coverage-optimized pipeline, this pipeline starts with comprehensive verification using model-based analysis to weed out configuration errors before changes are pushed to production.

- Operational state analysis: We next jump straight to operational state analysis. Since the emulation stage has been eliminated, the ability to find device software bugs before configuration is deployed is lost. Additionally, due to the risk of outages in production, it is not feasible to test how the network will react to failures. But if model-based analysis has comprehensively looked for configuration errors, the risk of major incidents in production is low.We can, however, regain some of the lost coverage against device software bugs through more post-deployment tests than in the coverage-optimized pipeline. In particular, in addition to unit tests that check the status of routing protocol sessions and interfaces, we can perform functional tests that we did earlier in emulation and are feasible to do on the production network. Such tests include:

- Checking that selected flows are blocked and forwarded as expected by running ping and traceroute.

- Comparing routing and forwarding tables in production to those predicted by model-based analysis.

Balancing coverage and resources

The two pipelines above optimize, respectively, for coverage and resources. In many cases, however, neither may be the appropriate solution. The coverage-optimized pipeline may be infeasible because it needs full-scale emulation, and completely removing emulation, as in the resource-optimized pipeline, may be undesirable.

One way to achieve a balance is via a scaled-down emulated environment that represents key aspects of the production network. This environment may even be customized to the change under test. For instance, if the change involves access control lists (ACL), the environment should have a device with the modified ACL.

Such a scaled-down environment can help uncover a class of device software bugs and is particularly helpful for detecting bugs in features that were previously not used in the network (because other features have been exercised heavily in the production network).

However, not all types of tests that can be run in full-scale emulation, can be performed with scaled-down emulation. For instance, we cannot check if the network reacts as expected to any device or link failure. This shortcoming may be acceptable if model-based analysis has already confirmed that failovers are configured correctly.

Pipeline comparison summary

The table below summarizes the coverage provided and resources needed by the three pipelines above.

| Coverage Optimized | Resource Optimized | Balanced | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coverage for configuration errors | Pre-deployment | Pre-deployment | Pre-deployment |

| Coverage for device software bugs | Pre-deployment | Post-deployment | Some pre-deployment, some post-deployment |

| Resources | High | Low | Medium |

You can build it today!

The validation pipelines above are not pipe dreams, but they can be built today using open source tools alone. Batfish can perform model-based analysis and verification; emulation engines such as GNS3 can emulate a variety of network devices; and a combination of NAPALM and TextFSM templates can help analyze the operational state of the network. Finally, automation frameworks such as Ansible and Salt can orchestrate and link these validation steps.

Even existing networks can be incrementally transitioned to such a pipeline. We will outline an approach for that in a future post.

By combining automation and validation, engineers will be able to rapidly evolve the network, securely and reliably. They can finally have a car that is both fast and safe.