Lesson from a network outage: Networks need automated reasoning

In the afternoon of October 23, within a few minutes of each other, two friends sent me a link to the recently-released “June 15, 2020 T-Mobile Network Outage Report” by the Public Safety and Homeland Security Bureau (PSHB) of the FCC. Given what Intentionet does, the report sounded interesting and I started reading it immediately.

The report details the massive impact of T-Mobile’s network outage. It lasted over 12 hours, and “at least 41% of all calls that attempted to use T-Mobile’s network during the outage failed, including at least 23,621 failed calls to 911.” The report also shares some individual stories behind the staggering numbers. For example, “One commenter noted that his mother, who has dementia, could not reach him after her car would not start and her roadside-assistance provider could not call her to clarify her location; she was stranded for seven hours but eventually contacted her son via a friend’s WhatsApp.”

“The outage was initially caused by an equipment failure and then exacerbated by a network routing misconfiguration that occurred when T-Mobile introduced a new router into its network.”

As someone who is working to eliminate such outages, parts of the report that discuss its root causes were illuminating. I learned that “the outage was initially caused by an equipment failure and then exacerbated by a network routing misconfiguration that occurred when T-Mobile introduced a new router into its network.”

Reading through the sequence of events that caused the outage, I could not help but conclude that this outage was completely preventable. T-Mobile should have known that their network is vulnerable to the failure and should have also known that the configuration change was erroneous before making the change.

Anatomy of the outage

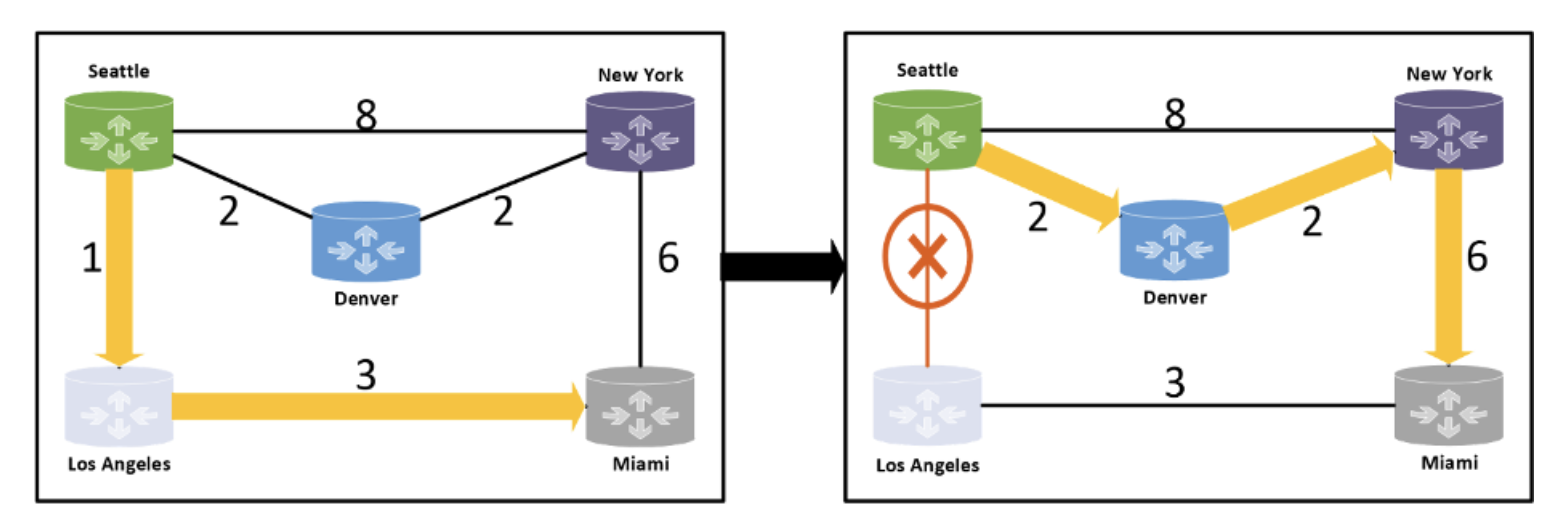

Let me explain using the same example network as the report, shown below. The network runs the Open Shortest-Path First (OSPF) routing protocol in which each link is configured with a weight and traffic uses the least weight path to the destination. The left diagram shows such a path from Seattle to Miami when all links are working, and the right diagram shows the path when the Seattle-Los Angeles link fails.

The notable thing is that the paths taken by the traffic are deterministic and knowable ahead of time, before any link weight is (re)configured or any failure occurs. For a large network, this computation tends to be too complex for humans, but computers are great for this type of thing.

For the T-Mobile outage, the first trigger was a link weight misconfiguration, which caused traffic to take unintended paths that were not suitably provisioned, thus causing an outage. This error could have been completely prevented by analyzing the impact of the planned change and ensuring that it did the right thing.

The second trigger was a link failure, which caused even more traffic to take unintended paths. This trigger was not preventable—equipment failures are a fact of life in any large network—but networks are designed to tolerate such failures. However, the fault-tolerance that T-Mobile thought existed in their network did not because of a configuration error. Whether this was due to the same misconfiguration as the first trigger or a different one is not clear from the report. In any case, the adverse impact of the failure could have been prevented by simulating failures and ensuring that the network responds correctly to failures.

Another factor behind the outage was a latent bug in the call routing software used by T-Mobile. It appears that the software had not been tested under the conditions induced by the events above.

Finally, T-Mobile’s attempts to alleviate the situation made it worse. They deactivated a link that they thought would divert the traffic to better paths but instead worsened the congestion. This also could have been prevented by analyzing the impact of link deactivation before deactivating it.

Automated reasoning to the rescue

While the outage was preventable, it would be unfair to pin blame on T-Mobile’s network engineers. Reasoning about the behavior of large networks is an incredibly complex task. Large networks have hundreds to thousands of devices, each with thousands of configuration lines. Judging the correctness of the network configuration requires network engineers to reason about the collective impact of all these configuration lines. Further, they need to do this reasoning not only for the “normal” case but also for all plausible failure cases, and there are a large number of such cases in a network like T-Mobile’s. It is simply unreasonable to expect humans, no matter how skilled, to be able to judge the correctness of configuration or predict the impact of changes.

To overcome these limits of human abilities, we must employ an approach based on software and algorithms, where the correctness of configuration and its response to failures is automatically analyzed. Fortunately, the technology to do this already exists. Tools such as Batfish, to which we at Intentionet contribute, can easily do this type of reasoning at the scale and complexity of real-world networks. As an example, see a blueprint we published last year on how failures can be automatically analyzed: Analyzing the Impact of Failures (and letting loose a Chaos Monkey).

Industry-wide change is needed

I certainly do not mean to single out T-Mobile. The problem is systemic and similar outages have happened at other companies as well. To list a few from this summer alone:

- IBM Cloud suffers prolonged outage

- Inadvertent Routing Error Causing Major Outage

- CenturyLink outage led to a 3.5% drop in global web traffic

- Cloudflare DNS goes down, taking a large piece of the internet with it

Based on my understanding of these outages, each was avoidable if effective and automatic configuration analysis using tools like Batfish were employed. In fact, studies show that 50-80% of all network outages can be attributed to configuration errors.

Modern society relies on computer networks, and this reliance has increased manifold this year as many of us have started working remotely. The networking community must respond by building robust infrastructure where outages are highly rare. We cannot continue to rely on human expertise alone to prevent outages and must start augmenting it systematically with automated reasoning. The hardware and software industries made this leap many years ago and experienced a dramatic improvement in reliability.

We have the technology and the ability, and we should have plenty of motivation. All we need is a collective will to fortify our defenses. It is time.